Minority rule still isn't normal

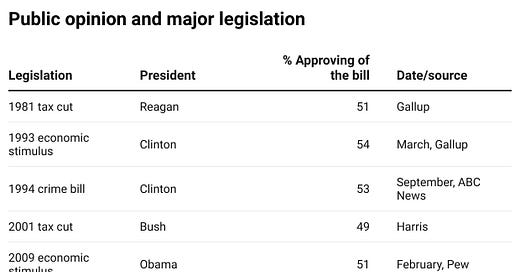

How does the "One Big Beautiful Bill" compare with public support for past legislation?

During Trump’s first term, it was easy to frame much of the administration’s agenda as minority rule. He had lost the popular vote, and thus, as multiple commentators pointed out, most Americans did not vote to be governed by the administration’s agenda. After the 2024 election, this has been a harder case to make: Trump did narrowly win the popular vote, and he’s certainly taken every opportunity to talk about the states and counties that he won, and to claim a sweeping mandate. Mandate narratives can be hard for commentators to resist, but winning the popular vote with a plurality doesn’t automatically make an agenda popular. And we have plenty of evidence that the Big Beautiful Bill passed on July 4 was not. Don’t take it from me – here’s a blog post from AEI about public opinion on the bill.

I know the big online discourses about the bill happened a few weeks ago, but I want to use this opportunity to tackle a big picture question that’s been bugging me since this spring, when one of my students asked me, “aren’t big pieces of legislation usually unpopular?” I responded: NO!, and promised to bring in some data on past bills, but promptly forgot. Professor of the year.

But I’ve returned to this question and done a medium dive here, because this question strikes me as one reflective of a larger shift in politics. Actually, I think if we look closer, it’s two important shifts. The first is a dynamic in which partisan divisions overwhelm any other political considerations. Plenty of scholars have tracked how this has changed the way bills are crafted and passed in Congress, and we see these manifest to some degree in public opinion. The bitterness of the politics over the Affordable Care Act, in particular, may have laid some groundwork for the second development. The second development is more concerning: an expectation, particularly among people whose political memories start in the 21st century, that the government will do things that are unpopular. The deeper undercurrent is that accountability is not expected and neither are efforts to meaningfully guide public opinion or build coalitions. This might be an accurate description of our current times, but it is hardly the historical norm in American politics. This post is meant to serve as a reminder – with the usual caveats that “normal” and “popular” are not guarantees for good, effective legislation, either.

Below, I show public support for a number of major bills, selected not all that systematically by me. Some came from the Roper iPoll archive, which is a database I accessed through my university library. The information on past tax bills comes from this highly informative article by Harry Enten from 2017. Other sources, as the table indicates, include KFF, Pew, and Fox News.

A few notes. First, while Bush tax cuts and the ACA were below majority support, they weren’t underwater – still more favorable than unfavorable. Second, it does seem like there’s a steady range for these bills – around a majority, give or take. Most of these were passed under unified government, and substantial numbers of Americans registered their disapproval. (Unfortunately, the era of floods of polling sort of coincides with the onset of partisan polarization, making it hard to draw valid historical comparisons, with, say, the legislation of the Eisenhower era or even the Great Society – though probably a more determined person could come up with more of that in the Roper archive). Third, the public likely had very different levels of knowledge about each of these bills, in ways that may be hard to fully track systematically. And for complex legislation like the ACA and this year’s bill, public opinion varies depending on the different provisions, and even how they are framed.

Public opinion isn’t everything. Popular legislation can certainly be mediocre or even quite bad. And we can certainly expect it to be divisive, especially along partisan lines. One case to consider is the USA PATRIOT Act, passed shortly after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. This legislation broadly enhanced government surveillance powers and is reviled by civil libertarians, but its popularity has fluctuated (through multiple legislative renewals). Weirdly, the earliest polling I could find was from August 2003, when it was pretty popular. Enjoy the 2003 internet graphics.) Public opinion can also feel touchy around issues of minority rights and protections – the ultimate in the elementary classroom banner “what’s right is not always popular, and what’s popular is not always right.” I did find some polling on the 1991 Civil Rights Act, which addressed some gaps in employment discrimination law, and was signed after an initial veto by George H. W. Bush in a period of divided government. According to a Newsweek/Gallup poll in April 1991, 41% of white respondents supported it while 9% opposed, and 51% of African Americans supported while 16% opposed. (African Americans were oversampled in the poll.) One takeaway is that more Black Americans were paying attention (over half of white respondents chose don’t know, compared with 33% of Black respondents). But even then, the bill had net approval among white respondents who offered an opinion, a good test case for the relationship between public opinion and policies that advance justice for disadvantaged groups.

Plenty of people have written about how and why the Trump/GOP bill has failed to appeal to majorities or even to large swaths of Republicans. The point here is much more about the apparent lack of fear of accountability, the lack of response to varied groups of stakeholders, and the spread of the idea that it’s standard for the government to put its coercive power behind policies many people dislike. Public support for major bills is often divided, and public attitudes change over time. That tells us that democratic governance is complicated and hard. We should still demand that our leaders try.