"Why doesn't somebody stop this?"

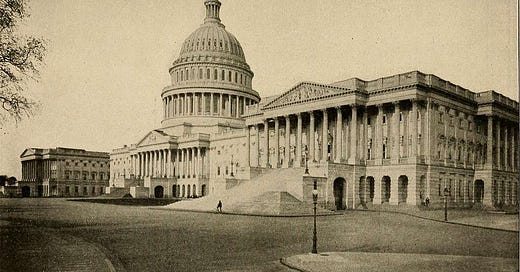

A little background on the Constitution and executive power

In just over a month, the Trump administration has established a dynamic in which they take unpopular actions driven by the executive branch, then pull back selectively in response to public outcry, court orders (maybe? sometimes?), or other forms of organized opposition. But they keep doing it, with actions that corrode the Constitution from multiple a…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good Politics/Bad Politics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.